This essay is published in tribute to Professor Pierre Dortiguier, who died on 5th July 2022 aged 81. Professor Dortiguier was a dedicated friend of Real History and the Real Europe.

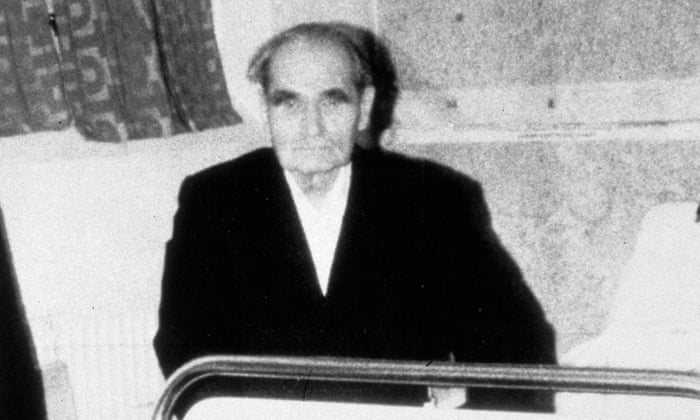

Recently released British government files take us a step closer to solving the mystery of the ‘suicide’ or murder of 93-year-old Rudolf Hess on 17th August 1987.

By the time of his death at Spandau Prison, Berlin – where he was the last remaining prisoner – Hess had been in captivity for more than 46 years, after he parachuted into Scotland on a peace mission in May 1941. Then aged 47, Hess had been Deputy Führer of Germany ever since Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933.

(On 26th April this year I published some of the letters that Hess wrote during the early stages of his captivity, indicating that he was far from irrational. Indeed he was arguably one of the most rational men in an irrational time.)

Some of the newly released documents cast further suspicion on Tony Jordan, the black American prison guard who was named some years ago by British historian David Irving as having murdered Hess. Irving’s information came from an interview with a Berlin prosecutor, but his conclusions are now additionally supported by documentary evidence, some of which is quoted for the first time in this article today.

Hess’s nurse was the Tunisian-born, German-educated Abdallah Melaouhi, who had held this post for three years and became a trusted confidant of the former Deputy Führer, due to his efficient and helpful conduct and because Hess (who was born in Egypt) was able to converse with him in Arabic.

On the morning of 17th August, Melaouhi attended to Hess’s morning exercises and medical tests in the usual manner, before going for his own lunch break. He was summoned from this lunch break some time after 2 pm and returned to the prison, which was by now in a state of emergency after Hess had been found dead or dying.

Hess’s usual habit after his lunch was to walk in the prison grounds, where he would sit in a “summer house” (actually a Portakabin), reading or dozing. When Melaouhi reached this summer house, he later stated “it looked as if there had been a wrestling match. …The seat on which Hess usually sat was overturned and was a long way from its usual position. Hess himself was lying lifeless on the ground: he showed no reaction. There was no measurable breathing, pulse or heartbeat. I thought he must have been dead for about 30 to 40 minutes.”

The words above come from a newly released copy of an affidavit by Melaouhi dated January 1989, though similar statements by him have long been in the public domain. What is being reported here for the first time are specific allegations that Melaouhi makes in his affidavit about Tony Jordan, a black American prison warder.

Spandau was a unique prison, under the joint control of the four Allied powers of 1945 – the UK, USA, Soviet Union and France (even though these had ceased to be ‘Allies’ and became Cold War rivals more then forty years earlier!). There were four Governors representing each of these Allies, and four sets of prison warders.

At any given time one of these ‘Allies’ was responsible for a garrison of soldiers guarding the prison, but these soldiers were not allowed to have any contact with the prisoner. They guarded the perimeter and did not set foot in the prison itself, which during each shift was run by three warders of different nationality: a Chief Warder, a cell block warder (who would be directly supervising the prisoner), and a warder on gate duty.

August 1987 was a month when the American garrison was on duty. On the afternoon of Hess’s death, the gate warder was British, the chief warder was French, and the cell block warder was the black American Tony Jordan.

In a January 1989 affidavit included in the newly released file, Melaouhi stated:

“An American guard called Jordan treated Hess particularly unpleasantly. Hess said that ‘Hell was usually let loose’ when he was on duty. He did not let Hess sleep at night. He refused everything Hess asked for. He met every request with insults and abuse which were coarse and grossly offensive.

“Hess regularly complained about this guard and the senior American guard Ahuja was told, but nothing happened. Then Mr Hess asked for a visit from the US Governor, Mr Keane. He made the same complaint to the Governor, in my presence. Hess was then told that Jordan was in an official post and could not be transferred. The other Governors knew about the complaints, but no action was taken.”

Melaouhi said that Hess had raised his complaint with the US General on the Allied Commission that controlled Berlin, saying that Jordan was “ill-mannered, impudent and had threatened him. He was so aggressive that he (Hess) had to appeal to the General for protection.”

These complaints were made in late April and early May 1987, just over three months before Hess’s death. Jordan was on holiday at the time, but on his return his “reaction when told about the complaint was extremely violent. He was called to see the General and at a meeting at which Governor Keane and Ahuja, the chief guard, were present, they obviously arrived at a solution which was designed ultimately to protect Jordan. Hess received a reply from the US General which more or less rejected his complaints.”

Melaouhi continued:

“The guards reacted accordingly and stepped up their pressure on Hess and their harassment. As a result he became depressed. The guards were now completely refusing to allow him any assistance. Consequently Hess’s physical state declined rapidly. At the end of April or early May he told me that he was going to die or be killed or poisoned soon. He specifically asked me at that time and in that connection to let his son, Mr Wolf-Rüdiger Hess, know if that happened, but he urged me not to tell his family anything about the harassment and mistreatment while he was still alive, because he was afraid the guards would take their revenge and mistreat him even more. He said, in so many words, ‘Then we will be lost and especially me, at the age of 93.’”

On being summoned to the prison from his lunch break on 17th August, Melaouhi spoke first to Bernard Miller, the British warder on gate duty.

“When I asked what was wrong, Miller said I could imagine: Jordan had been at work. The whole thing was finished and over.”

When he examined Hess’s lifeless body, the nurse recorded:

“On the right side of his neck under his ear I found that there were two red pressure marks about 8 cm long that looked as if they had been made by fingers. Jordan was standing near Hess’s feet and was obviously beside himself. He was sweating profusely, his shirt was soaked with sweat and he was not wearing a tie. Because of the dress and duty regulations this was unusual. I asked Jordan: ‘What have you done to him?’, whereupon he answered, in exactly these words, ‘The pig has been dealt with. You won’t need to do night duty any more.’”

Despite the situation seeming hopeless, Melaouhi attempted resuscitation and a medically qualified American soldier assisted him in trying to restart Hess’s heart. He then accompanied his patient in an ambulance to the nearby British Military Hospital, where Hess was certified dead.

Within weeks, an investigation by the Special Investigations Branch of the British Military Police had concluded that Hess committed suicide, and this verdict was hastily accepted by all four ‘Allies’.

We should bear in mind that when Hess had been sentenced to life imprisonment at the infamous Nuremberg trial, the Soviet judge had been the only dissenter – he argued that Hess should face the death penalty, but was outvoted by his British, American and French counterparts.

Exactly a month after Hess’s death, on September 17th, a British soldier from the Royal Engineers drove a bulldozer into the summer house where Spandau’s last prisoner had died. The Portakabin was smashed to pieces, petrol was poured over the remains and they were set alight. The British Governor of Spandau, Tony Le Tissier, threw into the flames the cord with which Hess had supposedly strangled himself.

When giving his sworn affidavit sixteen months later, Melaouhi was unconvinced by the suicide argument.

“Looking at the facts objectively, I think the story that he committed suicide is unlikely. The cord Hess is supposed to have strangled himself with – the only one there – was on a light and was only 70 cm long. In Hess’s bedroom and bathroom there were several much longer cords which would have been much more suitable if Hess had intended to commit suicide in this way, especially the electric cord in the bathroom. The cord in the summer house, as I last saw it, was hanging loose and had a knot in it.

“…I think from remarks that Hess made and from my own observation that Jordan had stolen some books from Hess. That might have led to a quarrel.

“…Hess was much more closely guarded in the summer house than in his cell. He would have been much more likely to commit suicide in the cell for that reason and also for the reason I mentioned before, that he would have had more suitable means of doing so. There does not seem to be any reason why Hess would have chosen the most unsuitable place if he intended to commit suicide.”

Regarding a supposed “farewell” or “suicide letter” in Hess’s handwriting, Melaouhi gave several reasons why he believed it could not be genuine and concluded:

“I imagine the letter was forged, by an American guard who could copy Hess’s signature and must have had an interest in cooperating with the action to back up Jordan.”

It is very obvious from the files that there was indeed a concerted effort to “back up” the black American guard. His fellow warders of all three nationalities used very similar phrases to exonerate him. For example Steven Timson, a British deputy chief warder who had been on holiday when Hess died, stated that although he had heard rumours of a complaint against Jordan, he had not witnessed any such incident and “as far as I know Mr Jordan has always been polite and fair in his dealings with the prisoner”.

Timson had very good reasons not to rock the boat. A year earlier he had stolen various personal items belonging to Hess that were supposedly held securely at Spandau, including the uniform that Hess had been wearing during his 1941 flight to Scotland. Eventually Timson was arrested after demanding 500,000 Deutschmarks from Hess’s son Wolf-Rüdiger for return of the items, but it’s significant that when the disappearance of these items was investigated in 1986 – by the Military Police Special Investigation Branch, the same force that was to investigate Hess’s death – they were unable to make any headway. The same wall of silence from Timson’s fellow warders blocked the theft investigation in 1986, just as it protected Jordan in 1987.

As with all ‘eye-witness’ testimonies, we are obliged to examine Melaouhi’s statements with due scepticism. It doesn’t help his case (though for reasons given below it was very understandable) that he refused to give a detailed statement during the weeks following Hess’s death. All he was prepared to say to the investigators was to describe his qualifications and duties, and to outline what happened during the last morning of Hess’s life when he attended to his patient in the normal fashion. He was unwilling to say anything at all about the afternoon’s events, and his 1987 statement says nothing at all about Jordan. When pressed at that time, Melaouhi stonewalled: “I am not willing to state anything further.”

It also doesn’t help that Melaouhi’s later statements (notably a 1994 affidavit almost seven years after the event) were selectively quoted by conspiracy theorists eager to promote an unlikely tale that British assassins had disguised themselves in American uniforms and smuggled themselves into the jail to kill Hess.

The newly released documents point to a much more likely course of events, and Melaouhi’s January 1989 statement would seem much more reliable than later embellishments.

Jordan disliked Hess and frequently bullied and threatened him. He was particularly incensed during the spring and summer of 1987 after Hess had made an official complaint against him. In conversation with Melaouhi, whom he had come to regard as a trusted confidant, Hess had specifically warned against pursuing the complaints further or mentioning them to his family, saying that the other warders would take Jordan’s side and then “we [my emphasis] will be lost and especially me, at the age of 93”.

Note the word “we”: Hess was well aware that Melaouhi, as a Tunisian, would have no powerful friends or allies in Berlin.

So when the worst happened, Melaouhi could see that Jordan’s fellow Americans would protect him. He refused to join in this cover up and give the sort of pro-Jordan cover story that other ‘witnesses’ signed up to, but he could see no point in recording his own story, until some sixteen months later he learned that Hess’s family had sought a second autopsy.

There are many other complications to the story of what happened in Spandau in August 1987, but the latest evidence points firmly towards Tony Jordan as the man with means, motive and opportunity. And also a man who could rely on supportive statements from his fellow prison warders, but not from the nurse Abdallah Melaouhi who was an honest and decent man, outside their ‘club’.

There never has been any serious evidence pointing to the alternative conspiracy theory, that British undercover agents disguised themselves as Americans in order to kill Hess.

This theory depends on the suggestion that Gorbachev’s Soviet Union was preparing to abandon its objection to Hess being released on compassionate grounds, and that the British secret state (having previously relied on Soviet intransigence) decided to kill Hess so as to prevent him revealing secret wartime discussions.

(A ludicrous version of the same conspiracy theory, put forward persistently by British Dr Hugh Thomas, suggests that the prisoner who lived for forty years in Spandau and died there was not Hess at all, but some sort of ‘double’.)

All of the emerging evidence suggests that by 1981, Britain was the most keen of the three Western Allies on pressing for Hess’s release, while the Soviet Union remained intransigent. Particularly important evidence involves an Allied agreement on how to dispose of Hess’s remains.

For more than twenty years there was agreement between all four Allies that Spandau prisoners should be buried within the grounds of the prison. In 1970, by which time Hess was the only remaining prisoner, a new agreement was reached, and the Allies accepted a Soviet suggestion that when Hess died he should be cremated, without consulting his family. Either the ashes would be scattered or they would be given to his family to be disposed of discreetly.

Partly for religious reasons the French were throughout the 1970s the most reluctant of the Allies to proceed with cremation, but in 1981 it was the British Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington (who for other reasons was often viewed by Israel as hostile to the Zionist state’s agenda) who became determined to defy Moscow and insist that when he died Hess’s body should be handed to his family.

For all his reputation as an anti-communist, Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of State – Alexander Haig – proved to be an appeaser of Moscow, seeking to soften Carrington’s line. Haig’s argument was that if the Russians continued to insist on cremation, the Western Allies should accept their view. Haig’s rationale exposes the US-Soviet interest in maintaining their duopoly in Europe: “I am sure you agree that both the viability of the Allied position in the city and the economic and spiritual well being of the Berliners are strongly tied, among other things, to our willingness to abide by the rules of the game as they have developed in numerous agreements and understandings with the Soviets since the occupation began.”

Haig stressed to his British counterpart that they should not “weaken the whole framework of custom and legality which has served as a basis for our position in Berlin”.

It was only after repeated pressure from Carrington and more than a year of further negotiation that the Americans and Soviets accepted Hess’s family were entitled to be given his body rather than a pile of ashes. Had London had a secret policy to kill Hess, they had ample opportunity before Nuremberg – and in the 1980s they would logically have acquiesced in the Soviet cremation policy, so as to ensure the destruction of evidence.

In a bitter irony, though the change of policy allowed Hess to be buried in a family grave in Wunsiedel, this entire family grave was eventually desecrated in July 2011 when the supposedly conservative German government of Angela Merkel proved itself to be more hardline than the now-defunct Soviet Union! The remains of the entire Hess family were cremated and the ashes scattered at sea.

Such was the German government’s fear (and its masters’ fear) of national-socialism more than 66 years after Adolf Hitler’s death!

Eventual British acquiescence in the cover-up of Hess’s murder – very likely committed by the black American prison warder Tony Jordan – has facilitated more complex conspiracy theories. But while they now appear to have no merit, there certainly is more than one guilty British secret to explore in relation to Rudolf Hess.

The entire Hess story of course reflects very badly on Churchill’s Britain, whom Hess approached with a sincere offer of peace, only to be treated as a war criminal, interrogated under torture and under the influence of drugs, and jailed for 46 years.

And was this dishonourable treatment even in Britain’s interests? Hess was after all offering a peace deal that would have left Germany free to destroy the true enemy of Britain and Europe – Stalin’s barbaric Soviet Union – while leaving the British Empire intact.

As Hugh Dalton, Churchill’s minister in charge of the ‘dirty tricks’ side of the war effort – the Special Operations Executive (SOE) – summarised the Hess mission in his diary on 16th June 1941:

“Hess said that the ground plan of Mein Kampf remains unchanged. Russia was the enemy, but England, if she wished, might still be the friend of Germany. Germany would take the Continent of Europe and England might have the rest of the world. Only some evil influences, in both countries, had deflected us from paths of cooperation and had, temporarily, led Hitler to follow other tactics than those which he had laid down in Mein Kampf.

“Hess thought that it would be a terrible mistake if English and Germans went on bombing each other when they might divide the world between them. He had come to the Duke of Hamilton because he was firmly convinced that, behind the facades of Parliament and Free Press, it was really the King and his Dukes who ruled England. Therefore, he must make a contact with one of this inner circle.”

British intelligence knew that Hess wasn’t mad. In fact for months British analysts had been predicting a German attack on the Soviet Union, and three days before Dalton’s diary entry above, senior MI5 officer Guy Liddell wrote in his diary:

“SIS [the British intelligence service MI6] report that the German advance on Russia will take place towards the end of this month.”

Indeed it did, on 22nd June 1941.

By rejecting Hess’s offer, Churchill ensured both the destruction of the British Empire and Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, with consequences that still loom over our continent in 2022.

More specifically, while there is no evidence that Britons (official or unofficial) killed Hess in Spandau in 1987, there most certainly was British involvement in a plot to kill Hess in England within months of his arrival.

I have examined the documentary trail of this plot, and its full implications will be discussed in my forthcoming book, but I shall give a brief summary here.

A fortnight before Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Guy Liddell of MI5 recorded that “certain members of the Polish forces in Scotland have been plotting to kidnap and murder Hess.” He assumed that their motive was “that Hess may be making peace overtures and that this will be listened to by the British Government. Nothing of course could be further from the truth.”

Within three weeks MI5 had compiled a full report into this “Polish plot” to kill Hess. The report itself is still highly classified – perhaps the best way for today’s British government to dispel notions of British involvement in killing Hess in 1987 would be to release these 1941 documents in full.

One problem might be that a particular sort of ‘Pole’ was involved in the 1941 plot to murder Hess – the same sort of ‘Poles’ or should we say (((Poles))) who later instigated the character assassination of the entire German people?

Moreover at least two important Britons were implicated in the plot. SOE officer Alfgar Hesketh-Prichard was an expert sniper, as his father had been before him. He also had close family ties to Zionist intelligence networks, which I discuss in detail in my forthcoming book. After his involvement in the abortive Hess murder plot, Hesketh-Prichard was assigned as SOE liaison with the team of Czech assassins plotting the murder of Reinhard Heydrich, which was carried out in Prague in May 1942.

At a more senior, backroom level, 51-year-old Lt. Col. Norman Coates was deputy chief of the prisoner of war department in London, and the direct superior of Col. Malcolm Scott who commanded ‘Camp Z’ where Hess was being held.

Coates was dismissed following the Hess investigation, when it was discovered that he had “been making money on the side”. He had a questionable financial record dating back to the 1920s when he had been bankrupted, and there was a suggestion of fraud involving the funds of (strangely enough) a Palestine Memorial Committee which was raising funds to erect a monument on the Mount of Olives. Coates had served during the First World War as Military Secretary to General Edmund Allenby, commander of British forces in the Middle East, whose campaign was greatly assisted by a still-mysterious Zionist espionage organisation known as the NILI Ring.

This was the type of Englishman who had top-level access to secret information about Hess and could be suborned by those with the most direct interest in making absolutely certain that there would be no Anglo-German peace deal.

On the credit side of the ledger, British security authorities made certain that this murder plot failed.

On the debit side, one reason why they did so is that they were confident Churchill’s government would not agree to Hess’s proposals. Zionist and ‘Polish’ representatives were evidently not so certain, or at least wanted to make absolutely sure by removing Hess from the equation.

Ever since 1941 British authorities have suppressed the truth about a plot to murder Rudolf Hess, even though Britain’s security service MI5 was responsible for foiling the plot. This suppression of evidence is because in the historiography of the Second World War certain people must always be portrayed as victims, never as perpetrators.

It now appears that ever since 1987 the four Allied powers have silenced the truth about Hess’s eventual murder – a murder which this time resulted not from a conspiracy but from the wilful blindness of prison authorities towards the violent tendencies of a negro guard. In the era of ‘Black Lives Matter’, who cares about the life of one of the 20th century’s greatest heroes, a man who sacrificed his life in a desperate effort to make peace between Britain and Germany?

Many other aspects of the Hess case and related matters will be discussed in Peter Rushton’s forthcoming book – keep checking this blog for details.

3 thoughts on “Solving the murder of Rudolf Hess”

Comments are closed.